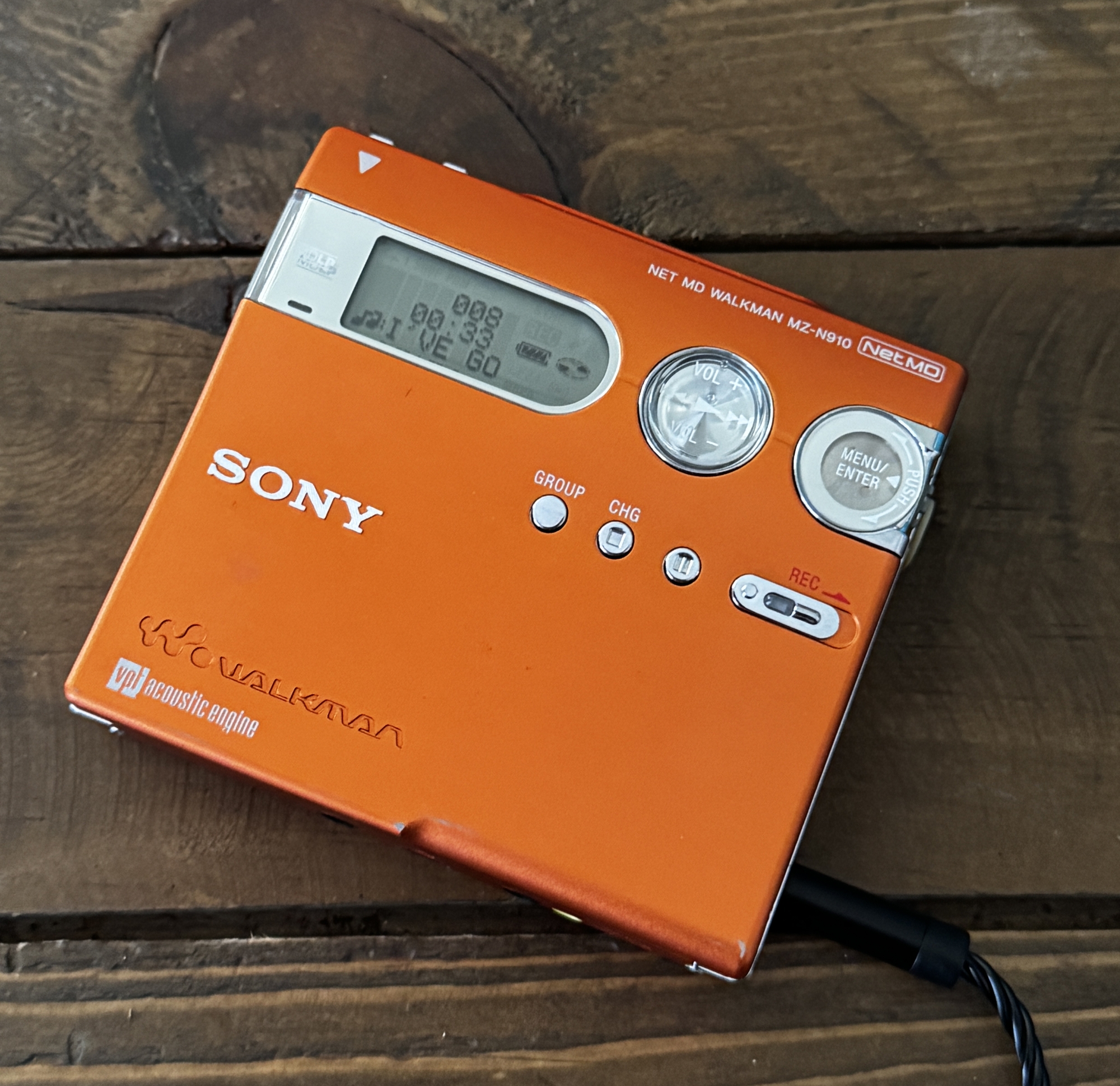

It Arrived…And It's Alive!

Very happy with my first foray into Japanese auctions! Upon arrival it powered up fine with an AA sidecar battery and/or power adapter, but wouldn't recognize a perfectly good, fully charged internal gumstick battery—nor would it charge said gumstick. Even though the contacts on the external battery door looked okay, I knew there had to be corrosion inside, so after shining a flashlight in the battery compartment and confirming the internal contacts were caked with the infamous green corrosion, I gingerly removed the rear case. Armed with vinegar, an old toothbrush, q-tips, and isopropyl alcohol—and having watched numerous videos on how to do it—I set about removing the green gunk. Afterwards I put it all back together—and to my utter amazement, not only did it still work, but now it recognized the gumstick battery and even worked! And that color! Sony sure knew how to do orange!

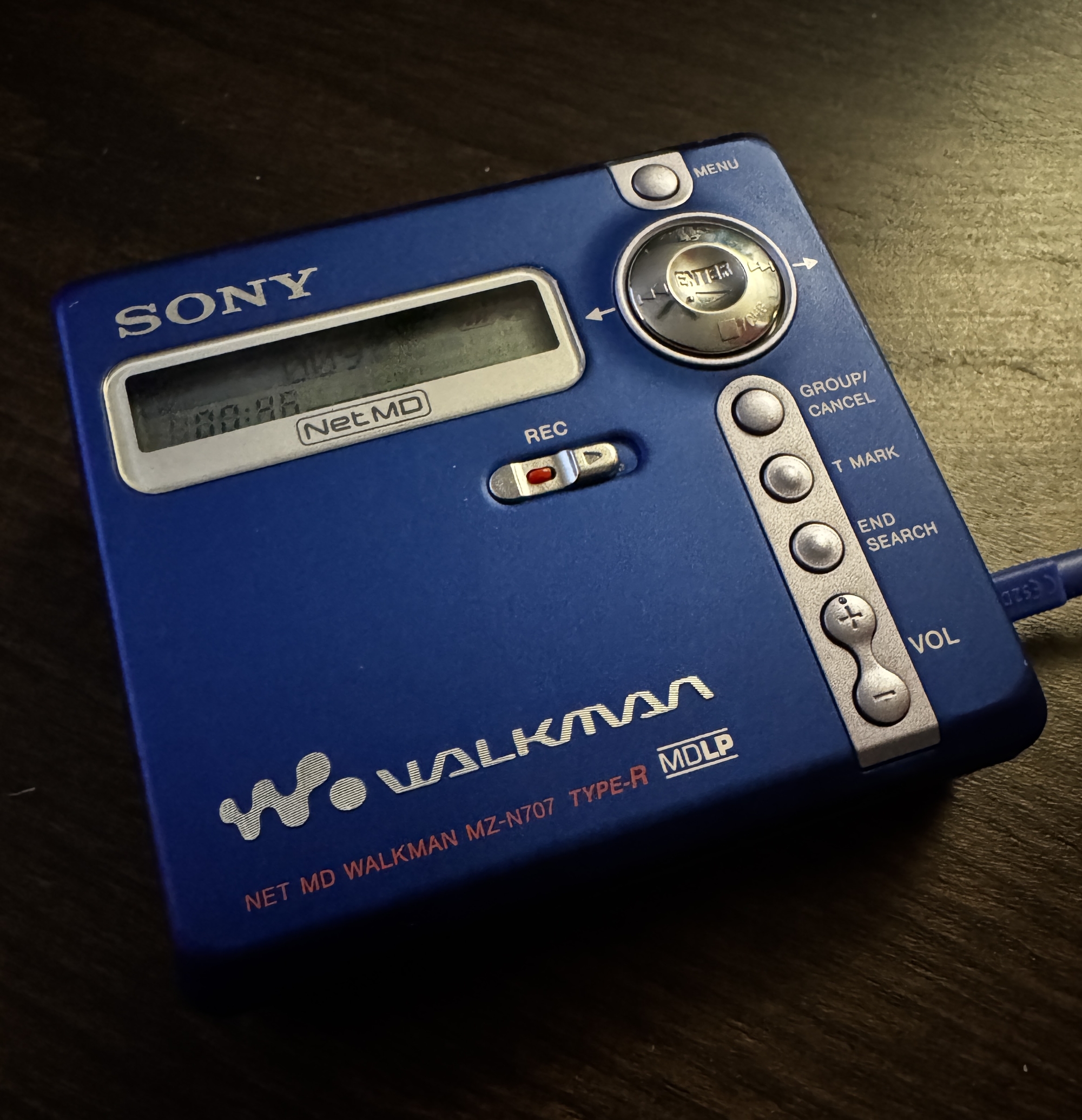

Of All My Nuggets…

…this one is undoubtedly one of my favorites. Sony was definitely at the top of their design game in the 90s and 00s, not only with Minidisc, but also with portable CD players.

For me, with the N707, it's the color, the design, the tactile feel of the unit. And the sound? Absolute chef's kiss. I can listen to this thing all day and never get burnt out. And of course, it works flawlessly. (Portable MD recorders/players, by their very nature, are much more complicated beasts than portable CD players and more prone to developing problems over years—especially if they've been neglected.)

PSA: If you're not going to use your portable electronics for an extended period and they have removable batteries, remove them.

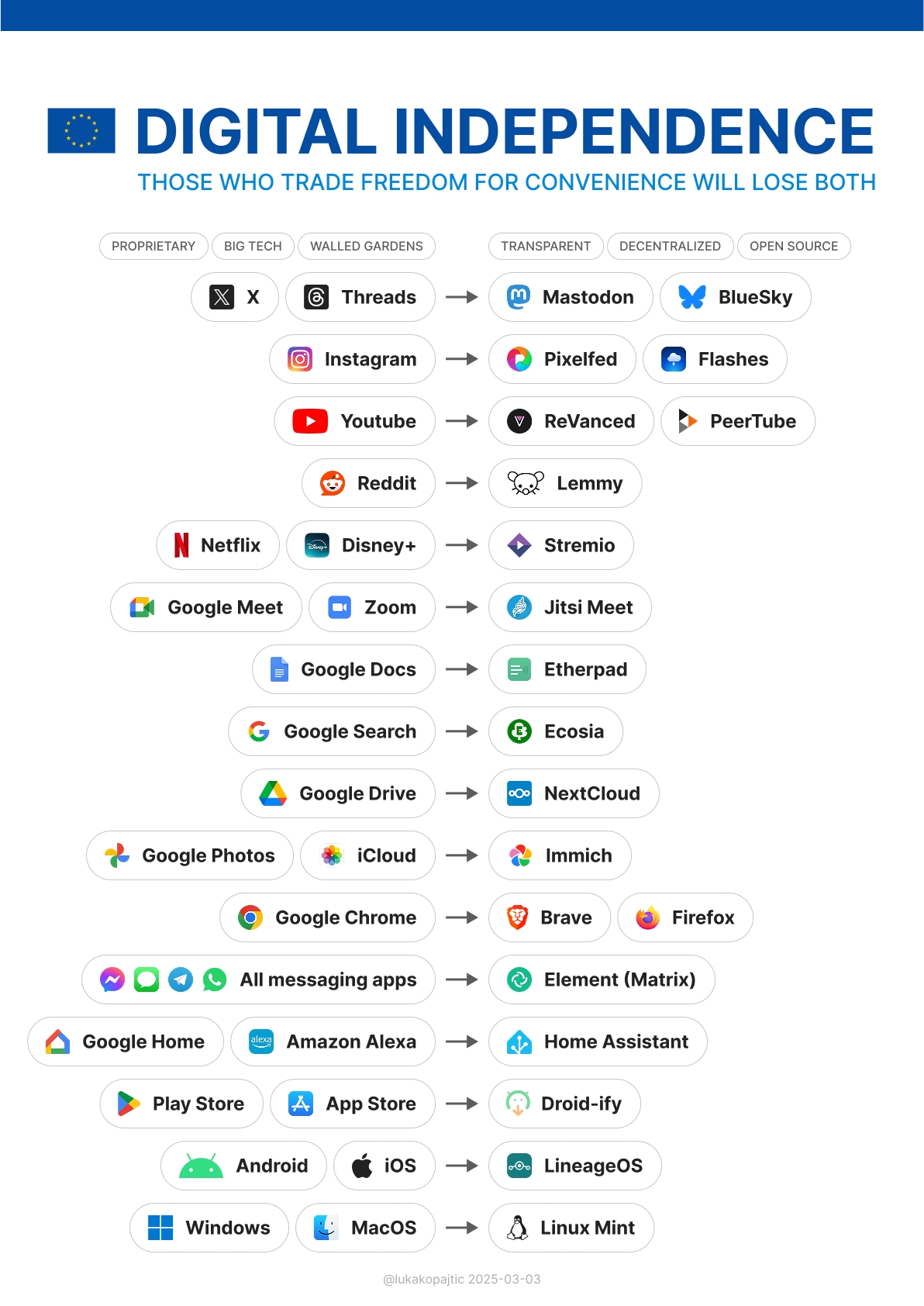

They're Not Wrong…

Apple propaganda notwithstanding, the reason tower PCs are big isn't because they're outdated. The reason tower PCs are so bulky is because they're designed to be user serviceable. The case has lots of open space so your big, meaty hands can easily access all of the components, and everything is secured with friction-fit tabs and standard machine screws to minimise the need for specialised tools. A properly laid out tower PC is fully serviceable with a single Phillips-head screwdriver and no greater manual skill than your average Lego playset – heck, for some of the more modern case layouts you don't even need the screwdriver, unless you're performing major surgery like a full motherboard replacement.

Like, think about who benefits from convincing you that a fully modular computing device that can be serviced and repaired with your bare hands and minimal technical skill is unfashionable.

Back in the day, I used to build my own PCs. I'd run down to Fry's Electronics, pick out a case, a motherboard, a CPU chip, memory, and whatever other components I needed. I'd drag it all home and assemble it myself. I'd load the O/S, power it up, and viola!

A Certain Aesthetic 😉

Late to the Party, As Usual

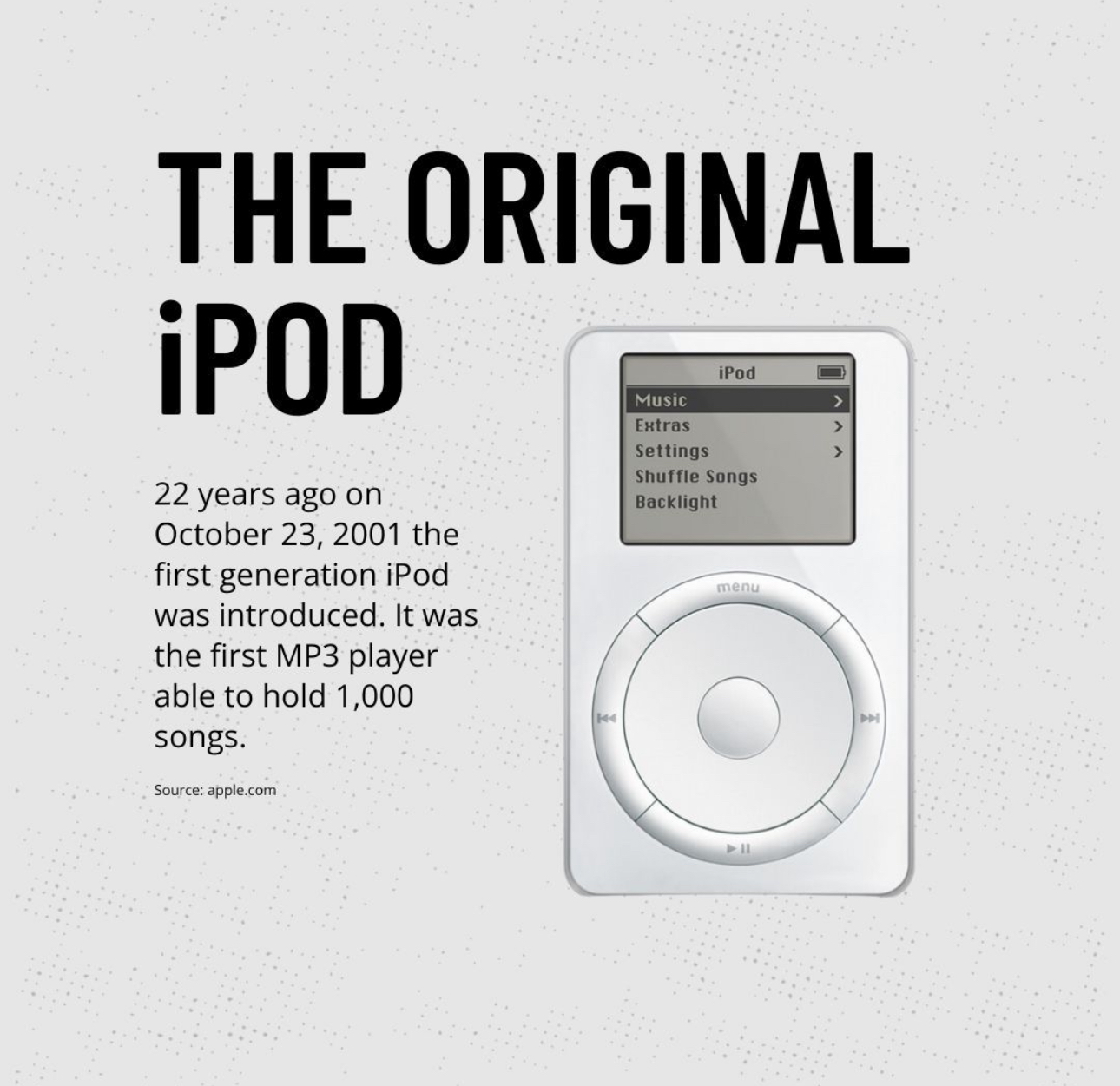

Back in early aughts, after receiving an unexpected windfall from the sale of some original Frank Lloyd Wright blueprints my dad gave me in the mid 80s that I'd been lugging around for over a decade, I used the funds and got into Minidisc in a big way—shortly before the time it was going to nosedive into irrelevance and obsolescence. (Hence the title of this post.) Despite the lukewarm reception the format received in the United States and the fact that it had been on the market since '92, I nonetheless adopted it wholeheartedly. I bought a portable player and a full-size deck to incorporate into my stereo system from The Sony Store that had popped up at The Metreon near Moscone Center in San Francisco. While CD-Rs/RWs were coming into their own by this time and it seemed everyone was still carrying around portable CD players (myself included), the iPod—and the ultimate death of MDs it hastened—were still a year away when I made my purchase. I didn't care about the format's relative obscurity even then; if nothing else, there was just a cool factor about MD and the players that I found irresistible.

Even after the iPod appeared, I stubbornly continued my love affair with the MD. I replaced my original portable MZ-E75 with the awesome MZ-S1 shortly after moving back to Phoenix in 2002, and a year later replaced my original MDS-630 deck with a MDS-480. Hell, I even put a Kenwood MD deck into my car. I amassed hundreds of those candy-colored shimmering plastic discs that I greedily filled up with not only the contents of my CD library at the time, but also music ripped from my burgeoning vinyl collection. At the time the discs were still plentiful, dirt cheap and recording was a breeze.

For years, I resisted jumping on the iPod bandwagon, believing the sound quality of MP3 files was subpar to ATRAC, which was used in encoding the MD format.

But then in March 2010, after listening to some music on Ben's iPod—and admitting the sound quality really was damn good—I broke down and bought my own. Not too long afterward—simply weighing the convenience of carrying an iPod containing my entire music collection versus all those discs, I sold my MD gear and practically gave away the discs.

I no longer have that iPod. I think I sold it when we were in Denver and I realized that most of the music I wanted to carry around with me could easily be swapped in and out of my phone. Having a separate device to do the same thing the phone could do was just…redundant. In the subsequent years, all of my listening has either been via vinyl on the "big" stereo in the living room or via headphones on my phone or Mac.

As y'all know, over the past eighteen months I've gotten back into CDs in a big way and they are still my preferred method of music consumption. I hadn't really thought much about Minidiscs until a few months ago when a MZ-S1 popped up in a post on Reddit and I was—as the kids say—consumed with the feels and it triggered something. Did I really want to get back into Minidisc, knowing what it would ultimately entail? Logically, it made no sense. Emotionally, the answer was a resounding, "We're about to descend into a dystopian hellscape, so why the hell not?" Still, I resisted the urge, but kept checking in on theMZ-S1 listings on eBay, gazing longingly and telling myself, no, no, no…

Until a week ago when I said fuck it.

Of course, the whole Minidisc landscape has changed over the past twenty years and getting back into it wouldn't be as simple as a trip to Best Buy or Fry's Electronics (which doesn't even exist any more). New players were no longer being made, and while new recordable media is still being manufactured by Sony, the variety and the "fun" factor of the disc designs has completely disappeared. If you want new, you basically have a choice of black on white or grey on white. Thankfully, there are still dozens and dozens of folks on eBay selling entire lots of used discs, and—since MDs can be rewritten "a million times" [according to Sony]—there are still plenty of options available to get all the media I'll ever want or need. On the whole, the hardware—both portable and deck variety—seems to have held up to the ravages of time much better than other "vintage" electronics, and can be found for cheap on eBay.

Which brings me to the present. I just received a MDS-JE480 deck that was in excellent condition that I snagged for a very reasonable amount of money. As of right now I have no remote control or media, but both should be arriving in the next few days. I also broke down bought a MZ-S1 portable that started this whole thing that's scheduled to arrive on Monday.

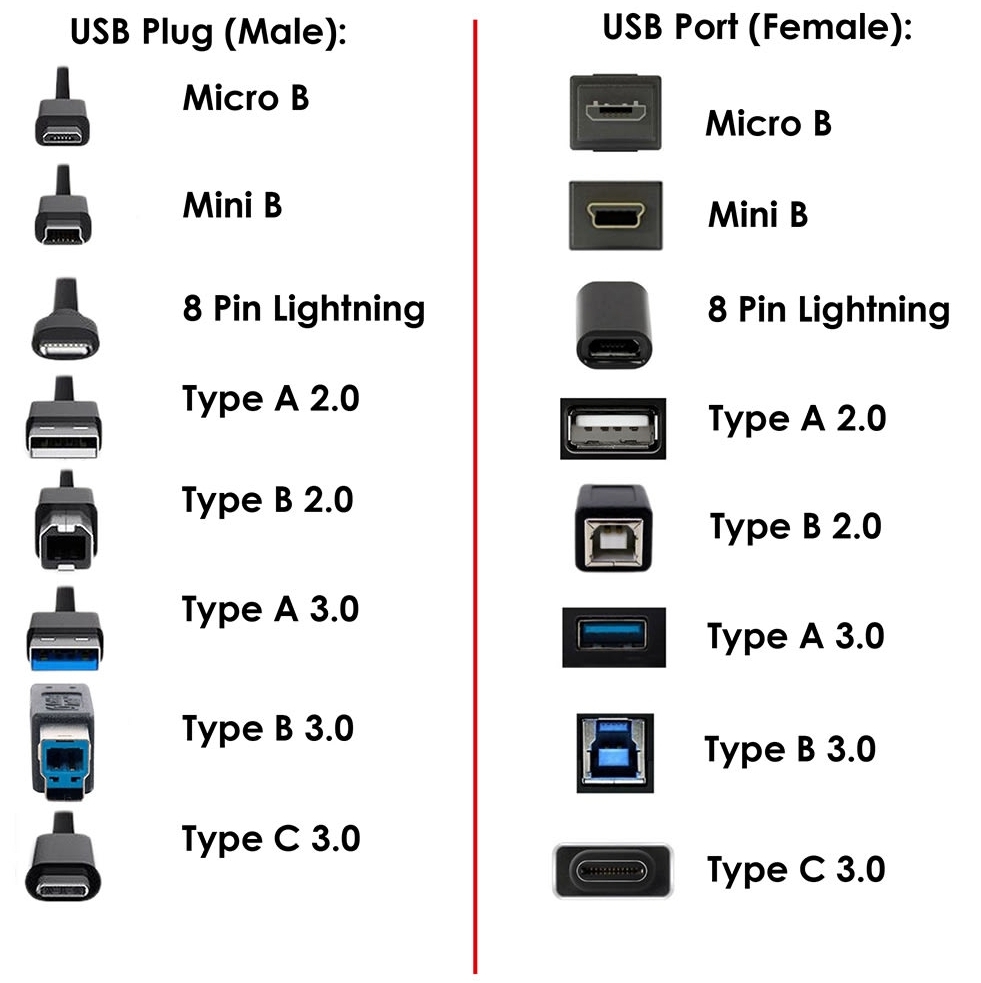

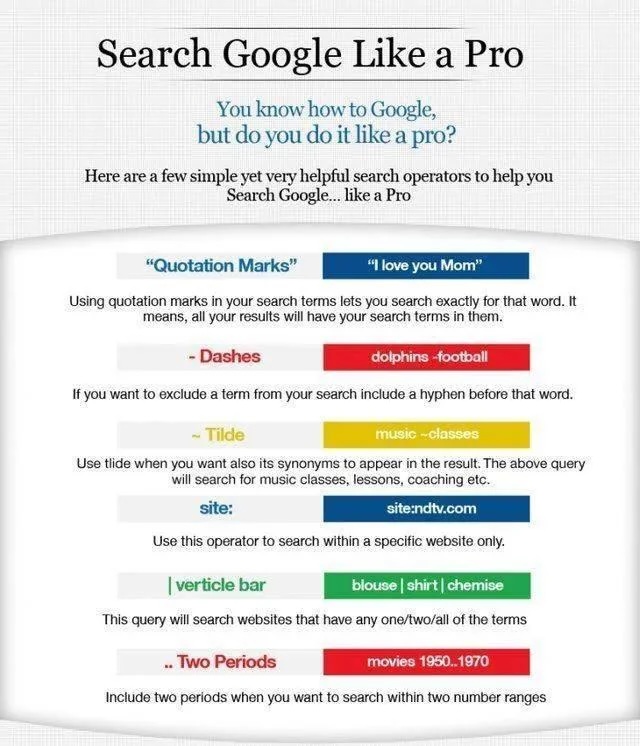

The More You Know…

I Don't Know What to Think of This One…

THIS RETRO OPEN-FRONT CD PLAYER ALSO HAS AN AMBIENT LAMP, FM RADIO, AND BLUETOOTH SPEAKER

They say history always repeats itself. Vinyls are making a comeback right now, which means in a few years cassettes and CDs will make a resurgence all over again, and when compact discs do enter the mainstream, you're going to be glad you had this cute CD player from Semetor. Spotted on the floor at IFA 2024, the K8 is a playfully retro CD player that embraces the design aesthetic of European appliances in the 50s. Designed with an open top that allows the CD to sit on its platter like a vinyl on a gramophone, the K8 comes with a few translucent typewriter-inspired buttons that let you control music playback. But wait, it's 2024, and just being a CD player obviously won't cut it… which is why the K8 also has an FM radio, a Bluetooth-enabled wireless speaker, and even an ambient lamp built into its adorable design.

Designer: Semetor

The K8 isn't a cutting-edge CD player… but it's cute. It has the adorable demeanor of one of lofree's older products, with its retro aesthetic that's brought about by its rounded form and use of pastel shades. What instantly grabs your eye first is the open-top CD player. While most players usually conceal the CD within a casing, this one does not. You see the CD spin as you play music, and the disc's radial spectral finish looks absolutely gorgeous.

Playback is easy. For running a CD, just hit the CD button on the panel, and use the controls below to play/pause, or skip tracks. A BT/FM button lets you toggle the Bluetooth player or FM radio. Backlights in the button glow to let you know which mode you're in, and a seven-segment LCD screen on the bottom allows you to see things like track number (for CDs) or radio station (for FM). A gold-plated 'gear' on the right side lets you switch on or off the K8.

If all that wasn't enough, the K8 also packs a warm glow-light for ambient lighting. Hit the button on the top right and a halo around the CD player lights up. It isn't enough to light a room, but it does bestow a warm wash of golden light in the immediate vicinity, perfect for late-night listening. Pair it with a nice soft jazz CD and you're absolutely set!

[Source]

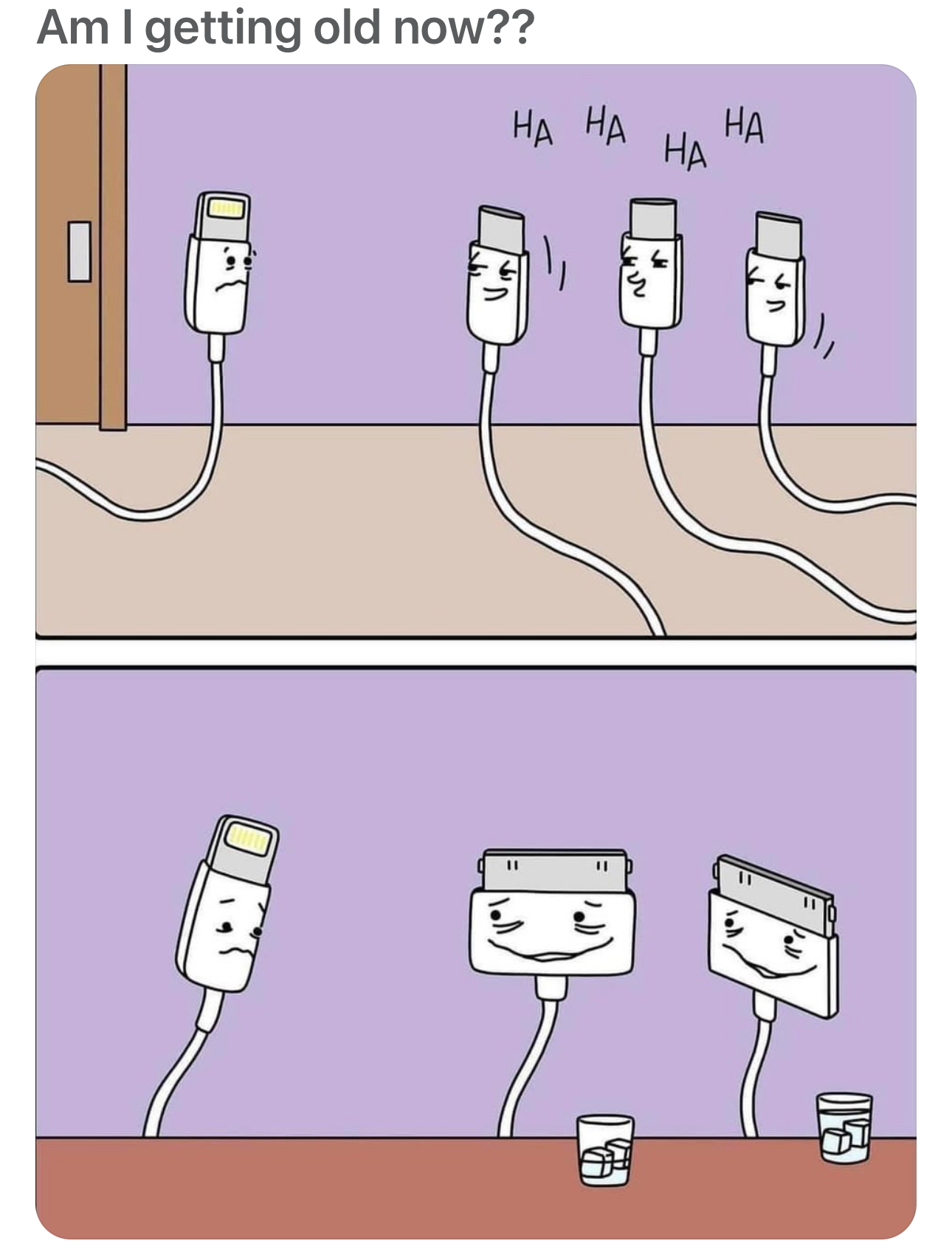

They've Become Sentient

I've Really Come to Admire…

Some Thoughts On Headphones

While they aren't my preferred method of listening to music, headphones have always played a big part in my musical enjoyment. I would not describe myself as a headphone geek in any sense of the word, but I do admit I have a great affinity for the buggers. Always have.

My love of headphones unsurprisingly began in the 70s, concurrent with my first tentative steps into HiFi with the Pioneer SE-205, a Christmas gift from my parents that had been on my holiday wish list. I don't remember much about these cans except they were big, heavy, and tended to put me to sleep when using them. But they afforded me the luxury of listening to my music loud long after my folks had gone to bed. (My bedroom was directly beneath theirs.) I do have two musical memories that stand out with these Pioneers, however: Elton John's Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy and Chicago's Chicago IX Greatest Hits. For some reason those two records are indelibly imprinted as being heard through these Pioneers—initially at least.

As my hi-fi journey continued, at one point not too many years later I encountered a pair of Stax electrostatic headphones at the local LaBelle's showroom. I was smitten. But at $450 ($1950 in 2024 dollars) they were way out of reach of my meager income. Stax did, however, offer a much cheaper, electret design at $150 ($650 in 2024 dollars) that sounded nearly as good and was actually something I could afford. Their only drawback was their need to be connected to my amp via an adapter box that attached to the speaker outputs on the amp. But the sound…oh my…these stayed with me for more than a decade. The weak point in their design however was the junction of the headphone cord with the earspeakers where the strain relief failed and the wiring broke. I can't tell you how many times over the years I had to disassemble them, trim off a bit of the cord past the break, and resolder the wires in place. I finally got tired of doing this and tossed them in the trunk of my car where they were eventually stolen. I purchased a "new" set a couple years ago after using many other brands and types since I originally owned them, and was frankly kind of disappointed. I still own them, but they're on a shelf and not even attached to my amp any more.

During the 1990s and early 2000s my hi-fi headphone listening via my main stereo amplifier took a break as I was distracted by my increasing use of portable music players of one kind or another and their supplied headphones/earbuds.

After I'd completed my radiation treatments in 2003, I decided I wanted to treat myself to something nice in celebration and I picked up a pair of Sony V-500s from Fry's Electronics. Damn, I loved those things. They weren't the most comfortable things in the world, but they sounded good and I kept them until the pads disintegrated and I threw them out prior to our move to Denver (I didn't know I could get replacement pads at the time, otherwise I'd probably still have them.)

With the acquisition of my first iPod and later iPhones of various iterations, all my headphone listening was on-the go, and I went through dozens of earbuds, (mostly Skullcandy), but my favorites were Apple's "Professional" earbuds—at least until they got rid of the headphone jack…

My first foray into Bluetooth headphones was prompted by Ben's purchase of a pair of Jaybird's Freedom earbuds. I tried them on, listened, and was immediately blown away by how much better they sounded than even Apple's Pro wired variety. I bought a pair. A year later, I upgraded them to Jaybird's Bluebuds X.

The Bluebuds X stayed with me until the first generation AirPods came on the scene. I remember scoffing at how earbuds without a cord were ripe targets for ending up in the washing machine, but looking back now I realize how ridiculous that was. By this time the batteries were precariously close to being shot on the Bluebuds, and while the batteries might've been able to be replaced, the lure of the new and shiny outweighed any thought of doing that.

I was surprised at the freedom the AirPods afforded, and while there was nothing wrong with them, when the AirPods Pro were released, it was a no-brainer to upgrade. For everything iPhone and Mac related my AirPods Pro remain my go-to listening device.

Last fall, I did want a more user-friendly listening experience for my main stereo system than the Stax electrets. I just wanted to be able to plug something into the headphone jack on the amp and listen away.

Based on recommendations from Dank Pods, I picked up a pair of Grado SR-60X from Amazon without even listening to them first, knowing full well if I hated them I could return them no questions asked.

Well, I didn't return them. Even though the SR-60X is considered the "entry level" of this line, these are seriously good-sounding cans. Grado is known for having a very distinctive sound, and that sound is very much to my liking. The SR-60X (and in fact, the entire Grado line) is also very customizable with different earpads, headbands, and even (if you're handy with a soldering iron) cables. My biggest complaints over the past few months have been one, the cable, and two, the earpads. The cable is braided. It's very heavy and not very pliant. It also tends to twist between the earspeakers and the Y-split. Untangling it is a pain. I've tried the three different varieties of OEM earpads that are available. The ones that initially came with the headset are fine for brief listening sessions, but they press too hard against my ears. While sounding better than the original pads, the over-the-ear design pads are ridiculously large and uncomfortable. The third variety that match the size of the original pads, but are of a donut design, sound great. What I found, however, is that the relatively rough foam they're made out of became so uncomfortable that I couldn't even stand to put them on any more. The open-back design also doesn't exactly lend itself to loud listening when you're in a room with someone else.

So this leads us to my latest set of headphones: the Sony MDR-7506. These have supposedly been made continuously since the 80s; they're Sony's professional workhorses. Again, I bought them from Amazon, thinking that if I didn't like them I could return them. At the time I couldn't remember the model number of my previous Sony headphones, so this was kind of a crap shoot to be honest.

At first I didn't like them. In fact, I went ahead and initiated a return. But as I wore them more and more they really came to grow on me. They fit snugly on my head without crushing my ears. The soft, coiled cord is a joy compared to the has-a-mind-of-its-own cord on the Grados. Unlike the Grados, these are closed-back cans, and they do a very good job of isolating your listening experience from the outside world. The sound is different from the Grados, but I like it just as much—if not, perhaps more. Upon recommendation I went ahead and ordered the optional YAXI L-R color-coded ear pads, and I have to say they are beyond comfortable.* I can easily see myself wearing these for an entire workday without any fatigue whatsoever. And I like the punch of color too.

So that's where I am at the moment. This post went on way longer than I originally envisioned, but if I'm passionate about something I do tend to ramble on.

*But they do—somehow—affect the sound (which has been documented) in a way I don't like, so for now I've gone back to the OEM pads.

Fuck You, Adobe

I've been an Adobe customer since…jeez…I don't even know. 2004? 2005?

Photoshop has been my go-to editing software, and Bridge (as rocky as that relationship has been over the years) has been my image organizing tool since before I was even a Mac user. But no more. I stumbled across this video the other day and it set my blood boiling:

I was unaware of this bit of assholery on Adobe's part, and like many others, just randomly clicked the "Accept" button after being presented with that splash screen without actually reading the terms and conditions. (I mean, who does?) After discussing this situation with Ben (we shared an Adobe subscription) and weighing our options, we decided to join the revolt and tell Adobe to go fuck itself once and for all.

Unfortunately…we had switched from the Full Creative Cloud Suite to just the Photoshop Plan a little over a month ago (just out of my get-out-of-jail-free period), and they were going to charge me $99 to cancel. I didn't have the funds to drop on that right away, but vowed that I would do it on the next paycheck.

Well, Ben located this today:

Guess what? It works! 🎉

I now use Pixelmator Pro (a one time purchase of $50 through the App Store, not $19.95/month as it was for Adobe Photoshop) for image editing/creation and XnView (free/donation) for image cataloging/organization. Pixelmator Pro has been a bit of a learning curve, but learning is always good, right? It doesn't have all the features of Photoshop (notably AI generation which I was using for creating backgrounds of smaller images on bigger canvases as well as ridding pictures of meddlesome text), but it's damn close. And as I wrote in that post from a few years ago, I've finally gotten XnView configured and customized totally to my liking and it doesn't randomly crash for no reason like every version of Bridge since it was first introduced.

These Gave Me A Whole New Appreciation For CDs

Having recently gotten back into CDs in a major way, I stumbled across this series of videos on YouTube and was captivated.

While even back in the day I had a general understanding of how this stuff worked, to this day it amazes me how any of this actually manages to work (and I've been a technophile my entire life). Forget the technobabble. It's voodoo and black magic, I say. Voodoo and black magic!

But You Are Blanche, You Are In That Chair!

Happy Birthday

I'd Rather Not…

Stuff I Didn't Know…

Those GUNS…

Meet Mike, my latest YouTube obsession… for obvious reasons. (And he can be spotted sporting a rainbow Apple Watch face in nearly all of his videos!)

Actually, his videos remind me of the very unpleasant history of early PCs that launched me on my career trajectory those many years ago. Looking back, it truly was stone knives and bear skins in comparison to today. MFM, RLL, selecting IRQs, terminating resistors; the crap we had to deal with! But at least we were treated like gods—or at least like first responders—for understanding how it all worked and getting the shit working again when it stopped.

Now it seems we're viewed as just janitors, cleaning up everyone else's mess because they're too intellectually lazy to even try and figure anything out on their own.

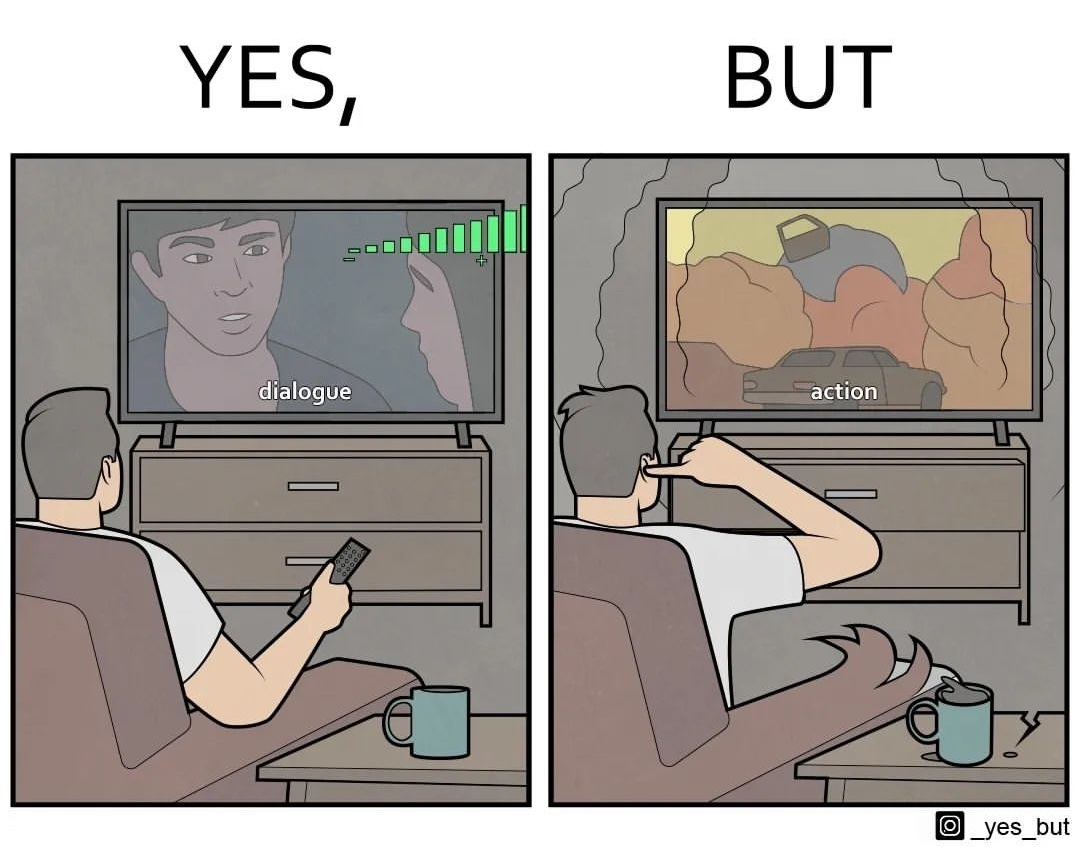

So It's NOT Just Me!

Interesting Geek Stuff

?

Those Were The Days

I remember how magic CDs used to be…

This Was an Accident

As you know, I've been participating in Apple's Public Beta programs for years. Early on (I think it was pre-Mavericks, actually) I learned the hard way that you do NOT install a beta on your main daily driver. Since that unfortunate mishap, I haven't stopped installing betas; I've just learned how to do it safely. Namely, by either installing on an external drive, or on a wholly separate partition on the main drive. The latter has been my preferred method for the last several iterations. And even then, I don't usually jump into the fray until Beta 3 or 4.

Well imagine my surprise when I saw the new MacOS Sonoma showing up as an available update in my System Preferences today. I guess you don't even need to be a member of the cordoned-off Public Beta program any more and—if you're foolhardy enough—to delve right into the Developer Beta Universe.

Okay, I thought. Why not? I'll create a separate partition and direct the installer to go there. Beta 1 is going to be fraught with danger, but it's safely tucked away from my critical data so what's the harm?

Well, it turns out this beta (and perhaps all developer releases?) doesn't follow the normal install routine. I clicked "upgrade" and it did not offer the customary screen prompting me where I'd like to install it. It simply rebooted and started installing.

Oh shit, I thought. Thankfully, I had last night's full-disk backup so I knew if I had to go back to Ventura I could. It wouldn't be pretty, and it would take several hours to reinstall the OS over the air and then restore all my data, but at least I had that safety net.

After about 20 minutes, the Sonoma install completed and brought me to the log in screen. "So far, so good," I thought. I logged in and everything came up normally.

Except…I had no internet connectivity. It showed I was connected via WiFi to my home network, but whenever I tried to go anywhere online I got notice that "You are not connected to the internet." I tried connecting via my phone's hotspot. I tried via the Cox shared network point. Nothing.

I turned off my VPN. I turned off the firewall. I turned off my ad blockers. Still nothing. Of course, there was not much info on the web about this yet, so after screwing around with it for about a half hour, I said fuck it, rebooted, wiped the drive, and two hours later Ventura was back up and running.

Today's Apple Product Announcement

For me, the creepiness factor of Apple's "Vision Pro" is off the charts. It's not just the look, but all the personal biomatric data it collects and processes—ostensibly in the name of maintaining your personal security.

While it's still a far cry from the device described in the final paragraphs below, I can easily see it ending up there at some point in the not-too-distant future.

A post I made in 2017 (skip to the "Brain Waves" section toward the end if you want to skip all the stereo geek stuff):

The Future of High Fidelity

I was cleaning stuff out over the weekend and ran across a file folder full of clippings I'd kept from various sources over the years. I was a big hi-fi geek in high school and college, and one of the articles I kept that I'd always loved was a bit of fiction from the mind of Larry Klein, published July 1977 in the magazine Stereo Review, describing the history of audio reproduction as told from a future perspective. Since the piece was written many years in advance of the personal computer revolution, the author was wildly off-base with some of his ideas, but others have manifested so close in concept—if not exact form—that I can't help but wonder if many young engineers of the day took them to heart in order to bring them to fruition.

And I would be very surprised indeed if one or more of the writers of Brainstorm had not read the section on neural implants, if only in passing…

Two Hundred Years of Recording

The fact that this year, 2077, is the Bicentennial of sound recording has gone virtually unnoticed. The reason is clear: electronic recording in all its manifestations so pervades our everyday lives that it is difficult to see it as a separate art or science, or even in any kind of historical perspective. There is, nevertheless, an unbroken evolutionary chain linking today's "encee" experience and Edison's successful first attempt to emboss a nursery rhyme on a tinfoil-coated cylinder.

Elsewhere in this Transfax printout you will find an article from our archives dealing with the first one hundred years of recording. Although today's record/reproduce technology has literally nothing in common with those first primitive, mechanical attempts to preserve a sonic experience, it is instruction from a historical and philosophical perspective to examine the development of what was to become known as "high fidelity."

Primitive Audio

It is clear from the writings of the time that the period just after the year 1950 was the turning point for sound reproduction. For a variety of sociological, economic, and technological reasons, the pursuit of accurate sound reproduction suddenly evolved from the passionate pastime of a few engineers and Bell Laboratories scientists into a multimillion-dollar industry. In the space of only fifteen years, "hi-fi" became virtually a mass-market commodity and certainly a household term. In the late 1970s, the first primitive microprocessors (miniature computer type logic-plus-memory devices) appeared in home audio equipment. These permitted the user to program was was known as an "FM tuner," record player," or "tape recorder" to follow a certain procedure in delivering broadcast or recorded material.

For those who are not collectors of those antique audio devices, which employed "records" or "tapes," such terms require explanation. From its earliest beginning, recording employed an analog technique. This means that whatever sound was to be preserved and subsequently reproduced was converted to an equivalent corresponding mechanical irregularity on a surface. When playback was desired, this irregularity was detected or "read" by a mechanical sensing device and directly (later, indirectly) reconverted into sound. It may be difficult to believe, but if, say, a middle-A tone (which corresponds to air vibrating at a rate of 440 times per second) was recorded, the signatl would actually consists of a series of undulations or bumps which would be made to travel under a very fine-pointed stylus at a rate of 440 undulations per second. Looking back from a present-day perspective, it seems a wonder that this sort of crude mechanical technique worked at all—and a veritable miracle that it worked as well as it did.

The End of Analog

Magnetic recording first came into prominence in the 1950s. Instead of undulations on the walls of a groove molded in a nominally flat vinyl disc, there were a series of magnetic patterns laid down on very long lengths of of thin plastic tape coated on one side with a readily magnetized material. However, the system was still analog in principle, since if the 440-Hz tone was magnetically recorded, 440 cycles of magnetic flux passed by the reproducing head in playback. All analog systems—no matter what the format—suffered the same inherent problem (susceptibility to noise and distortion), and the drive for further improvement caused the development of the digital audio recorder.

Simply explained, the digital recording technique "samples" the signal, say, 50,000 tiles a second, and for each instant of sampling it assigns a digitally encoded number that indicates the relative amplitude of the signal at that moment. Even the most complex signal can be assigned one number that will totally describe it for an instant in time if the "instant" chosen is brief enough. The more complex the signal, the greater the number of samples needed to represent it properly in encoded form.

In the late Seventies and earl Eighties, digital audio tape recording proliferated on the professional level, and slightly later it also became standard for the home recordist. Many of the better home videotape recording systems were adaptable for audio recording; they either came with built-in video-to-audio switching or had accessory converters available.

The video disc, first announced in the late 1960s, progressed rapidly along its own independent path, since it benefited from many of the same technical developments as the other home video and digital products. B the mid 1980s a variety of video-disc player were available that, when fed the proper disc, could provide both large-screen video programs with stereo sound or multichannel audio with separate reverb-only channels. The fat semiconductor RV screen that was available in any size desired appeared in the early 1980s. It was the inevitable outgrowth of the light-emitting diode (LED) technology that provided the readouts for the electronic watches and calculators that were ubiquitous during the early 1970s. Later in the decade, giant-screen home video faced competition from holographic recording/playback technique. Whether the viewer preferred a three-dimensional image than was necessarily limited in size and confined (somewhat) in spatial perspective or a life-size two-dimensional one ultimately came down to the specifics of the program material. In any case, the two non-compatible formats competed for the next twenty years or so.

LSI, RAM, and ROM

By the late 1980s, the pocket computer (not calculator) had become a reality. Here too, the evolutionary trend had been clearly visible for some time. The first integrated circuits were built in the late 1950s with only one active component per "chip." By the end of the Seventies, some LSI (large-scale integrated circuit) chips had over 30,000 components, and RAM (random-access memory) and ROM (read-only memory) microprocessor chips became almost as common as resistors in the hi-fi gear of the early 1980s. ADC's Accutrac turntable (ca. 1976) was the first product resulting from (in their phrase) "the marriage of a computer and an audio component." The progeny of this miscegenation was the forerunner of a host of automatic audio components that could remember stations, search out selections, adjust controls, prevent audio mishaps, monitor performance, and in general make equipment operation easier while offering greater fidelity than ever before. As a critic of the period wrote, "This new generation of computerized audio equipment will take care of everything for the audiophile except the listening." Shortly thereafter, the equipment did begin to "listen" also, and soon any audiophile without a totally voice-controlled system (keyed, of course only to his own vocal patterns) felt very much behind the times. One could also verbally program the next selection—or the next one hundred.

"Resident" Computers

The turn of the century saw LSI chips with million-bit memories and perhaps 250 logic circuits—and the eruption of two controversies, one major and one minor. The major controversy would have been familiar to those of our ancestors who were involved in the cable-vs-broadcast TV hassles during the 197os and later. The big question in the year 2000 was the advantage of "time sharing" compared with "resident" computers for program storage.

Since the 1950s the need for fast out put and large memory-storage capacity had drien designers into ever more sophisticated devices, most of them derived from fundamental research in solid-state physics. The late 1970s, a period of rapid advances, saw the primitive beginnings of numerous different technologies, including the charge-transfer device (CTD), the surface acoustic-wave deivce (SAW), and the charge-coupled device (CCD), each of which had special attributes and ultimately was pressed into the service of sound reproduction processing and memory. The development of the technique of molecular-beam eipitaxy (which enabled chips to be fabricated by bombarding them with molecular beams) eventually led to superconductor (rather than semiconductor) LSIs and molecular –tag memory (MTM) devices. Super-fast and with a fantastically large storage capacity, the MTM chips functioned as the heart of the pocket-size ROM cartridge (or "cart" as it was known) that contained the equivalent of hundreds of primitive LP discs.

The read-only memory of the MT carts could provide only the music that had been "hard-programmed" into them. This was fine for the classical music buff, sicne it was possible to buy the complete works of, say, Bach, Beethoven, and Carter in a variety of performances all in one MT cart and still have molecules left over for the complete works of Stravinsky, Copland, Smythe, and Kuzo. However, anyone concerned with keeping his music library up to date with the latest Rama-rock releases or Martian crystal-tone productions obviously needed a programmable memory. But how would the new program get to the resident computer and in what format?

By this time, every home naturally had a direct cable to a master time-sharing computer whose memory banks were contantly being updated with the latest compositions and performances. That was just one of its minor facilities, of course, but music listeners who subscribed to the service needed only request a desired selection and it would be fed and stored in their RAM memory units. Those audiophiles who derived no ego gratification from owning an enormous library of MT carts could simply use the main computer feed directly and avoid the redundance of storing program material at home. Everyone was wired anyway, directly, to the National Computer by ultra-wide-bandwidth cable. The cable normally handled multichannel audio-video transmissions in addition to personal communication, bill-paying, voting, etc., and, of course, the Transfax printout you are now reading.

Creative Options

The other controversy mentioned, a relatively minor one, involved a question of creative aesthetics. The equalizers used by the primitive analog audiophiles provided the ability to second-guess the recording engineers in respect to tonal balance in playback. This was child's play compared with the options provided by computer manipulation of the digitally encoded material. Rhythms and tempos of recorded material could easily be recomposed ("decomposed" in the view of some purists) to the listeners' tastes. Furthermore, one could ask the computer to compose original works or to pervert compositions already in its memory banks. For example, one could hear Mongo Santamaria's rendition of Mozart's Jupiter Symphony or even A Hard Day's Night as orchestrated by Bach or Rimsky-Korsakov. The computer could deliver such works in full fidelity—sonic fidelity, that is—without a millisecond's hesitation.

Since Edison's time, the major problems of high fidelity have occurred in the interface devices, those transducers that "read" the analog-encoded material from the recording at one end of the chain or converted it into sound at the other. Digital recording, computer manipulation of the program material, and the MT memory carts solved the pickup end of the problem elegantly; however, for decades the electronic-to-sonic reconversion remained terribly inexact, despite the fact that it was known for at least a century that the core of the problem lay in the need to overlay a specific acoustic recording environment on a nonspecific listening environment. Techniques such as time-delay reverb devices, quadraphonics, and biaural recording/playback, which put enough "information" into a listening environment to override, more or less, the natural acoustics, were frequently quite successful in creating an illusion of sonic reality. But it continued to be very difficult to establish the necessary psychoacoustic cues. The problem was soluble, but it was certainly not easy with conventional technology. And the necessary unconventional technology appeared only in the early years of this century.

Brain Waves

It has long been known that all the material fed to the brain from the various sense organs is first translated into a sort of pulse-code modulation. But it was only fifty years ago that the psychophysiologists managed to break the so-called "neural code." The first applications of the neural-code (NC) converters were, logically enough, as prosthetic devices for the blind and deaf. (The artificial sense organs themselves could actually have been built a hundred years ago, but the conversion of their output signals to an encoded form that the brain would accept and translate into sight and sound was a major stumbling block.)

The NC (encee) converter was fed by micro-miniature sensors and then coupled to the brain through whatever neural pathways were available. Since rather delicate surgery was required to implant and connect the sensory transducer/converter properly, the invention of the Slansky Neuron Coupler was hailed as a breakthrough rivaling the original invention of the neural code converter. The Slansky Coupler, which enabled encoded information to be radiated to the brain without direct connection, took the form (for prosthetic use) of a thin disk subcutaneously implanted at the apex of the skull. Micro-miniature sensors were also implanted in the general location of the patient's eyes or ears. Total surgery time was less than one hour, and upon completion the recipient could hear or see at least as well as a person with normal senses.

What has all this to do with high-fidelity reproduction? Ten years ago a medical student "borrowed" a Slansky device and with the aid of an engineer friend connected it to a hi-fi system and then taped it to his forehead. Initially, the story goes, the music was "translated"—"scrambled" would be more accurate—into color and form and the video into sound, but several hundred engineering hours later the digitally encoded program and the Slansky device were properly coupled and a reasonable analog of the program was direcly experienced.

When the commercial entertainment possibilities inherent in the Slansky Coupler became evident, it was only a matter of time before special program material became available for it. And at almost every live entertainment or sports event, hi-fi hobbyists could be seen wearing their sensory helmets and recording the material. When played back later, the sight and sound fed directly to the brain provided a perfect you-are-there experience, except that other sensory stimuli were lacking. That was taken care of in short order. Although the complete sensory recording package was far too expensive for even the advanced neural recordist, "underground" cartridges began to appear that provided a complete surrogate sensory experience. You were there—doing, feeling, tasting, hearing, seeing whatever the recordist underwent. The experience was not only subjectively indistinguishable from the real thing, but it was, usually, better than life. After all, could the average person-in-the-street ever know what it is to play a perfect Cyrano before an admiring audience or spend an evening on the town (or home in bed) with his favorite video star?

The potential for poetry—and for pornography—was unlimited. And therein, as we have learned, is the social danger of the Slansky device. Since the vicarious thrills provided by the neural-code-converter/coupler are certainly more "interesting" than real life ever is, more and more citizens are daily joining the ranks of the "encees." They claim—if you can establish communication wit them—that life under the helmet is far superior that that experienced by the hidebound "realies." Perhaps they are right, but the insidious pleasures of the encee helmet has produced a hard core of dropouts from life far exceeding in both number and unreachablility those generated by the drug cultures of the last century. And while the civil-liberties and moral aspects of the matter are being hotly debated, the situation is worsening daily. It is doubtful that the early audiophiles ever dreamed that the achievement of ultimate high-fidelity sound reproduction would one day threaten the very fabric of the society that made it possible.

OMG…

Brain melts. pic.twitter.com/DWFZy7JQL0

— Aysha Ridzuan (@ayshardzn) March 24, 2023

This whole Tiktok hearing in Congress reinforces my belief in that we need an entry requirement for politics (just like any company out there) to ensure better and smarter politicians lead the country. Basic knowledge of the internet and technology in general should be a requirement. Some of the questions during the hearing were so elementary and mind-numbingly stupid.

I Had One of These

The second-generation Sony D-100 was my second portable CD player. The first was a first-generation Sony D-7. Being an early adopter, I suffered through several problems with the D-7, but it was worth it to have "CD Quality" sound with me wherever I went.

The D-100, however, was much more reliable and was my constant companion for half a dozen years or so. The only problem it had was a dodgy headphone jack that kept coming unsoldered from the main circuit board, necessitating numerous self-repairs over the lifespan of the unit.

I don't remember what ultimately happened to either player, but my need for a portable CD player was eventually usurped when I got into Minidisc in the late 90s and the early 00s; a technology vastly superior for portable music, but ultimately made obsolete by the iPod.

Right There With Ya, Buddy

That's Been My Experience

Ours Isn't Nearly as Creative

Le Sigh

This Sony model was the last portable Minidisc player I owned. I got big into MD in the late 90s/early 00s. I had [more than one] MD deck, a MD player in my car, and of course, various portables. I hung onto the format until I got my first iPod and when I started using iTunes, I knew MD—as wonderful a format as it was—was dead. The hardware was awesome, but Sony's software was absolute shit. I eventually sold off all my gear and the hundreds of disks I'd amassed, never looking back.

Every now and then, however, an image like this crosses my path and I just sigh.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Ben was also into MD. I mean, what are the chances of that?