Based on some recent incidents, let me reiterate: If you are the owner of a photo that appears on this site and wish it removed, you don’t need to get all legal and send threatening letters and takedown notices; just email me with the photo’s URL or leave a comment on the offending post and I will gladly remove it.

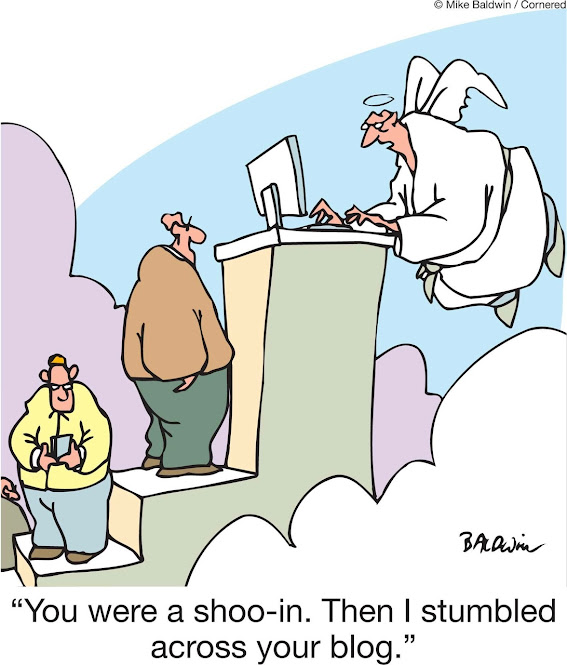

In other words…

Mark Alexander

You’re a bad man. You’re a very bad man!

Irreverent, independent, and often snarky partnered married gay boomer and doggie dad who is tired of moral pontification by hypocritical conservative assholes and hate filled religious bigots.

This blog is NSFW and intended for adults only.

It may contain unapologetically liberal diatribes and photos of naked men, either alone or together, doing things that may cause inexplicable erections among certain sanctimonious anti-gay Republican congressmen. In addition to my personal photography, images displayed here have been pulled from the internet.

I think there is more to it than this rather simple flow chart. Another point of view:

https://humanparts.medium.com/the-power-of-prayer-in-an-agnostic-life-b0e43bf2e1cd

The Power of Prayer in an Agnostic Life

It’s not about religion. It’s about being honest with yourself.

Dakota Morlan

Dakota Morlan

Aug 30, 2020·8 min read

It was Christmas Eve, but it sure didn’t feel like it.

The previous Christmas Eve, I’d watched a midnight Mass outside the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. I suppose it couldn’t get any more “Christmas” than that. But there had been snipers on the rooftops protecting the gathering from an ISIS threat — their eerie silhouettes surrounding Jesus’ supposed birthplace (which I’d recently learned was up for debate). And even without that added touch, the truth was that the Palestinians just didn’t celebrate Christmas like we did at Gramps’ condo in Sacramento.

But I was back with my family for this Christmas. For all intents and purposes, everything was the same as it had been for the past 20 years. The highly anticipated steak and lobster dinner, the jazz, the gilded jesters covering the sizable fake tree, and our polite and tedious present-opening beneath it — they all happened just as planned. Everyone involved, whom I’d missed last Christmas, was still alive and in relatively good health. Nothing had changed. But as I sat alone beside the tree in the fading afterglow of the evening, I realized that I had.

Christmas no longer held the magic of an infallible ritual. Whatever sensations and sentiments I’d associated with the holiday since infancy were illusions kept alive by my loved ones — and they were so very fallible, so very vulnerable.

Between the time I had finished my semester abroad and arrived at this Christmas Eve, I had spent a summer studying in Nice, France. That summer brimmed with French wine, freedom, and the warm waters of the Mediterranean. But that summer was also when a homicidal ISIS recruit drove a truck through crowds of people on Bastille Day.

Eighty-six people died, and hundreds were injured. A classmate of mine — a handsome Berkeley student from Italy — had been left laying on the pavement for hours before his body was identified. It had rained that night, and an image of him crumpled and unclaimed wouldn’t leave my mind. It was blazing in my head when his parents flew out the next day to stand vigil with us, and I could scarcely stand it. A week later, at the top of a mountain overlooking the city, my friend told me he’d never be the same after what he’d seen on that promenade, and I agreed.

Lying in bed the night before this Christmas Eve, I delivered an ultimatum to God, who had been earning less of my trust and attention for months: “Whatever you are, if you exist, and if there is any goodness within you, show me a miracle tomorrow, or I will never believe in you again.”

Christmas Day had come and gone, the pie eaten, the cousins gone, and although I was feeling abysmal, I’d forgotten about my prayer. That is, until I took a last scroll through Facebook and saw this headline: “Christmas Miracle Comforts Parents of Nice Terrorist Attack Victim.”

A few days earlier, the parents of the deceased Berkeley student had learned that two local women had stayed with him on the pavement all night long, surrounding him with candles and praying through the rain. They had learned the news just in time for their first Christmas without their son. His parents intended to track down the women and thank them.

I don’t pray very often, though I should. There have only been a handful of times I’ve asked God for some kind of sign or intervention. Perhaps, psychologically, I never want to ask God for more than I believe possible because I don’t want to be disappointed or selfish. If he doesn’t save the sick child of praying parents, why should he help me with my chemistry exam?

What Happens When Our Prayers Don’t Work?

Maybe we’re seeking the wrong answers

humanparts.medium.com

My relationship with God has been inconsistent at best. I discovered God in my adolescent years through the fervent teachings of a Southern Baptist youth group. My evolution into a rational adult brought the growing pains of divorcing my concept of a higher power from some damaging ideas I once nurtured.

When I do pray, it’s more often a form of meditation. As I fall asleep, I list all the things that I’m worried about and all the things I’m thankful for. I then ask God to take care of what’s out of my hands. It is incredibly cathartic and comforting to humble myself before God (or the universe or whatever word you choose to define that higher power) and truly realize how much is beyond my control and, therefore, not worth worrying about.

For me, talking to God evokes a powerful feeling of love, acceptance, and connection within me. It helps me focus on what I need to do, whether I want to or not, because it removes my ego from the conversation. There is no use in lying to God or myself.

Beyond the emotional comfort, some studies have shown that the act of praying can help in terms of healing health problems largely associated with stress — although ultimately the science remains inconclusive. More interestingly, prayer may be associated with all the benefits stemming from the “placebo response,” — reconceived as a powerful mind-body phenomenon — yielding potential significant treatment gains.

So it seems prayer is likely good for us. But what about those times when our prayers lead to inexplicable coincidences — or even “miracles”?

My “miracle from God” during Christmas 2017 was not the first I experienced. When I was 12 or so, my grandfather lost his battle with cancer while I was away at science camp. The funeral was held just days later, and not wanting to pull me out of the experience, my parents left me at camp. I’m sure I agreed with their decision at the time, but in the weeks to follow, my guilt over missing the funeral and never telling my grandpa I loved him ate me up inside. To me, he’d always seemed kind of grumpy, and it wasn’t the kind of relationship for verbal affirmations. But I did love him. And every night for weeks, I prayed to God to let him know that.

Then, one night, I had a dream. I was in a space of complete nothingness, but the nothingness was filled with white light and a feeling of absolute peace that I’d never experienced before. In that space was my grandpa, healthy and handsome with all his hair, and he was smiling at me.

“I love you, Grampy,” I said.

“I know,” he replied.

We hugged, and I could feel the texture of his polo shirt and smell the familiar detergent. It was unlike any other dream I’ve ever had, and in my mind, it still remains the last time I ever saw my grandpa. I didn’t regret missing the funeral again after that.

Of course, there are the “miracles everywhere” people, who swear they receive divine images on their toast or that a certain song on the radio told them to invest in real estate. It’s easy to scoff at these people, especially when God doesn’t similarly intervene in the direst of circumstances. Their loved ones still die, they suffer from chronic illnesses, and they don’t seem to be any luckier than the rest of us.

But how we choose to see the world can shape our own reality and that of others — for better or worse.

Maybe a sign from God is really a message sent from one’s own deepest self, rooted in desires that we may or may not be consciously aware of.

In 2004, when Marvin John Heemeyer was fortifying his Komatsu bulldozer to demolish the town of Granby, Colorado, for the perceived wrongs its residents had committed against him, he said that it was God’s will. He believed that every step in his planning and preparation would have been thwarted if God had not wanted him to follow through. Maybe God wanted Heemeyer to cut gun ports into his bulldozer, endanger the lives of many, commit millions of dollars of damage to a city, and die by suicide in the driver’s seat. Or maybe Heemeyer, at the core of his being, wanted to commit those acts and chose to believe it was God’s will.

Many crimes carried out by religious people have involved “instruction from God.” I wonder if the driver in the Nice attack, who was willing to die for his cause, believed he had received such signs. Or if he ignored them.

We can’t know what is really going on in other people’s heads. But perhaps we can conclude that a person’s prayer is only as good as their own moral character — that a sign from God is really a message sent from one’s own deepest self, rooted in desires that we may or may not be consciously aware of.

On that Christmas Eve, had I not prayed to God the night before, would I have seen that fateful Facebook article? I don’t know. But I do know that I would not have considered it a miracle, and I might not have experienced the profound hope that it gave me.

Prayer is a superpower we can access to better understand ourselves and our place in the world, and we don’t have to be religious to do it.

In my heart of hearts, I want to believe in a benevolent, omnipotent force. I want to believe that life is worth living, in part, for these moments of divine revelation. And I think I’m a better person for it.

My theory of prayer may seem reductive, but it isn’t meant to be.

The human brain is an expanding enigma, and everything we experience — even a genuine miracle from God — must pass through it, be translated and interpreted by it. If signs from God are really a heightened awareness of our own inner selves, an organic organ providing us with a transformative experience, then what could be more divine?

Prayer is a superpower we can access to better understand ourselves and our place in the world, and we don’t have to be religious to do it.

My own ideas of God are continually evolving. Of late, I’ve begun to think of him as the fiber that holds us all together. The Force. That voice in your head that tells you to do the hard thing because it’s the right thing. The middle-of-the-night idea that takes on a life of its own and rides you around until you see it through. An epiphany. A serendipitous quote from Goldie Hawn. An apology and forgiveness. The Dalai Lama saying for the billionth time that altruism is the root of happiness, and this time it sticks. It’s admitting you’re wrong. Learning a better way. It’s peace in knowing you will do all you can and nothing more.

Prayer, either for oneself or others, is an act of love. If done in earnest, it’s an act of unadulterated honesty. Love brings more love. Honesty brings insight. Insight yields real change. I think we could all use a little more of that.