Every. Damn. Day.

Once a legitimate blog. Now just a collection of memes 'n menz.

Every. Damn. Day.

…this is going to be a very unpopular opinion for bleeding heart liberals like myself, but after making a trip to the local Target for groceries today, I'm beginning to think that maybe the herd needs to be culled and humanity needs a purge after all.

Except for the store employees, myself and a very few others, no one was wearing masks. No one (including Target employees, who seem to insist on stocking the shelves when the store is busiest and blocking aisles in the process) was observing the 6-foot rule. I tried, but it seemed no matter where I stopped to look at my list or answer a text, some yahoo was standing next to me within a matter of seconds. And people were touching everything.

I asked three different employees the location of a particular item. I got three different responses, all incorrect. It was only when I opened up the Target app on my phone and searched myself did I find what I was looking for.

Like last weekend, the amount of Saturday traffic was near normal, indicating the people are not staying home except for essential trips out of the house. And it seems that during the four (six?) weeks of stay-at-home orders, most of the population has forgotten how to fucking drive.

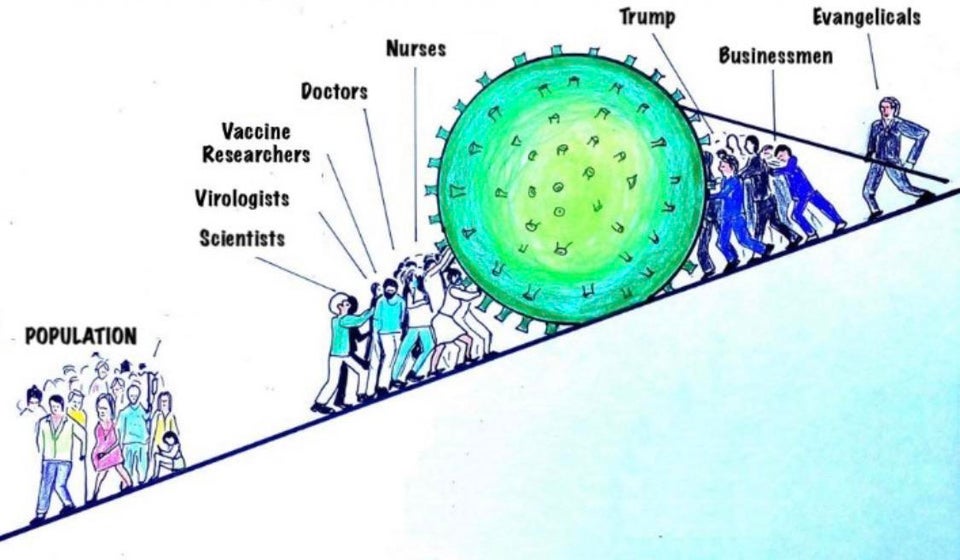

If it takes a pandemic to rid the species of the willfully ignorant, then so be it. Let them congregate in their churches. Let them gather together on statehouse steps and scream that businesses be reopened. Hell, let Trump's lickspittle Republican governors open their states and ensure that when a second wave of Corona hits in October, it will further reduce the number of the Orange Baboon's voters; his "very fine people."

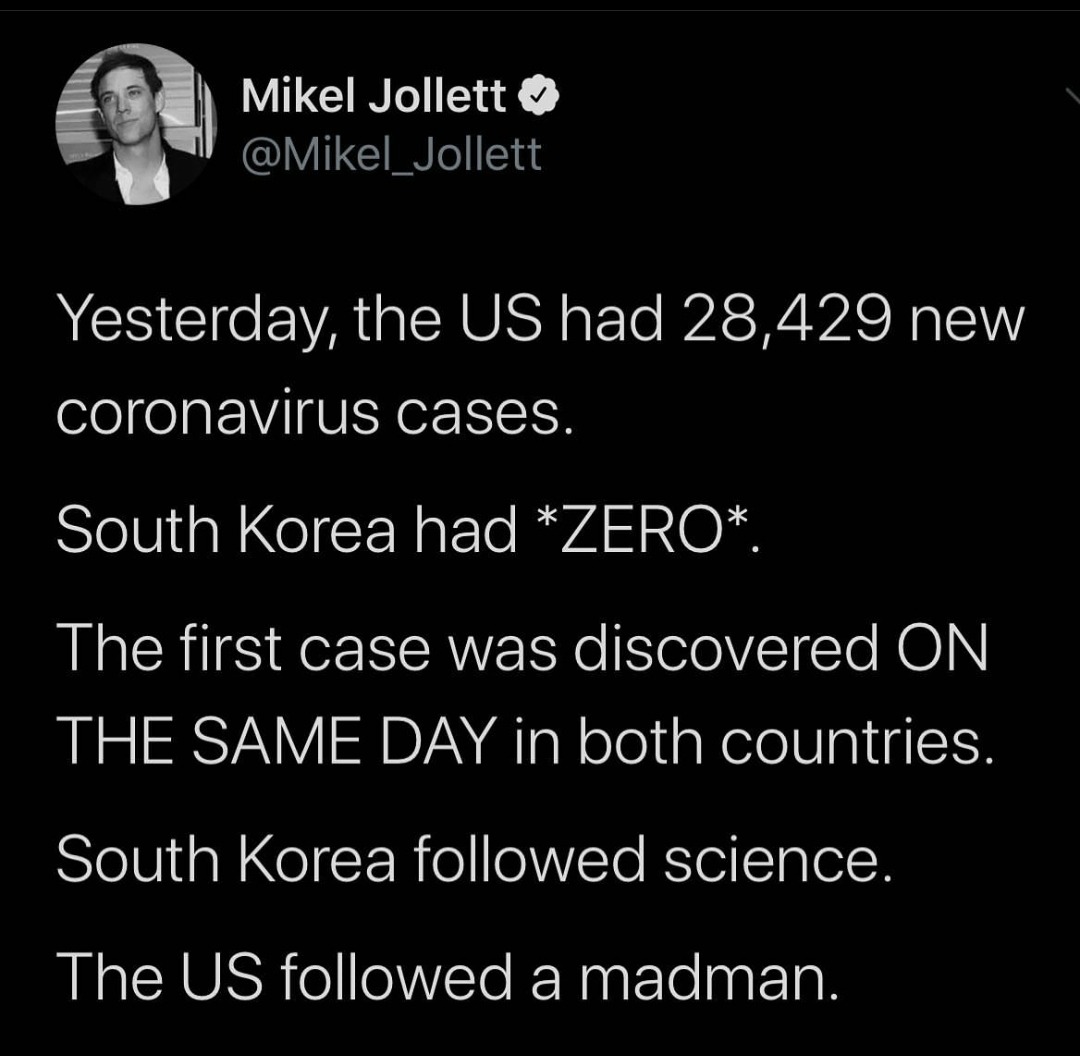

And this, my friends, is why the Orange Russian Wig Stand still has a 40% approval rating. Even now.

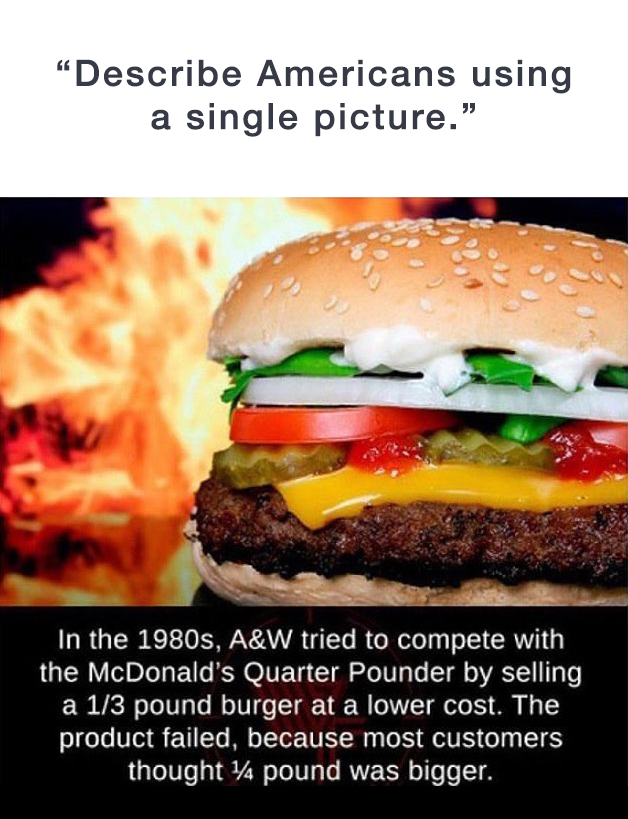

Let me explain why I like to pay taxes for schools even though I personally don't have a kid in school. It's because I don't like living in a country with a bunch of stupid people." ~ John Green

Let me explain why I like to pay taxes for schools even though I personally don't have a kid in school. It's because I don't like living in a country with a bunch of stupid people." ~ John Green

[source]

Nothing could be worse than a return to normality. Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

Nothing could be worse than a return to normality. Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world, and ready to fight for it." ~ Arundhati Roy

She gets it. And it makes my heart flutter.

History repeating…

From NBC News:

When the clock struck noon, the masks came off.

It was Nov. 21, 1918, and San Francisco residents gathered in the streets to celebrate not only the recent end of World War I and the Allies' victory, but also the end of an onerous ordinance that shut down the city and required all residents and visitors to wear face coverings in public to stop the spread of the so-called Spanish flu.

A blaring whistle alerted gratified residents across the city and, as the San Francisco Chronicle reported at the time, "the sidewalks and runnels were strewn with the relics of a torturous month," despite warnings from the health department to maintain face coverings. As celebrations continued and residents flocked to theaters, restaurants and other public spaces soon thereafter, city officials would soon learn their problems were far from over.

Now, amid the coronavirus pandemic, as President Donald Trump urges the reopening of the country and some states, such as Georgia, move to resume normal business even as new cases emerge, how officials acted during the 1918 flu pandemic, specifically in cities such as San Francisco, offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of doing so too soon.

Alex Navarro, the assistant director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan, which detailed historical accounts of the 1918-19 flu pandemic in 43 cities, told NBC News in a phone interview that officials often acted quickly at the time but restrictions were eased to varying degrees.

"There was a lot of pressure in pretty much all of these American cities to reopen," said Navarro, whose research was done in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "When they removed those restrictions too soon, then many cities saw a resurgence in cases."

The center's research found that cities that used "early, sustained and layered" practices such as social distancing, closing public events and stay-at-home orders "fared better than those that did not."

'A lot of stock in masks'

Just two months earlier, in September, the first case of the so-called Spanish flu was identified in San Francisco and city health officials sprung into action.

Dr. William C. Hassler, the city's health officer, ordered the local man who apparently brought the disease to the city after a trip to Chicago into quarantine to stop the disease from finding another human host, according to the center's research of reported accounts.

But it was too late as the virus had already begun to make its way through the city. By mid-October, the cases jumped from 169 to 2,000 in just one week. Later that month, Mayor James Rolph put in place social distancing practices and met with Hassler, other health officials, local business owners as well as officials from the federal government to discuss a plan to close the city.

Some officials demurred at the idea, worried about damage to the city's economy and the risk of causing public panic. Eventually, on Oct. 18, the city voted to shut down "all places of public amusement."

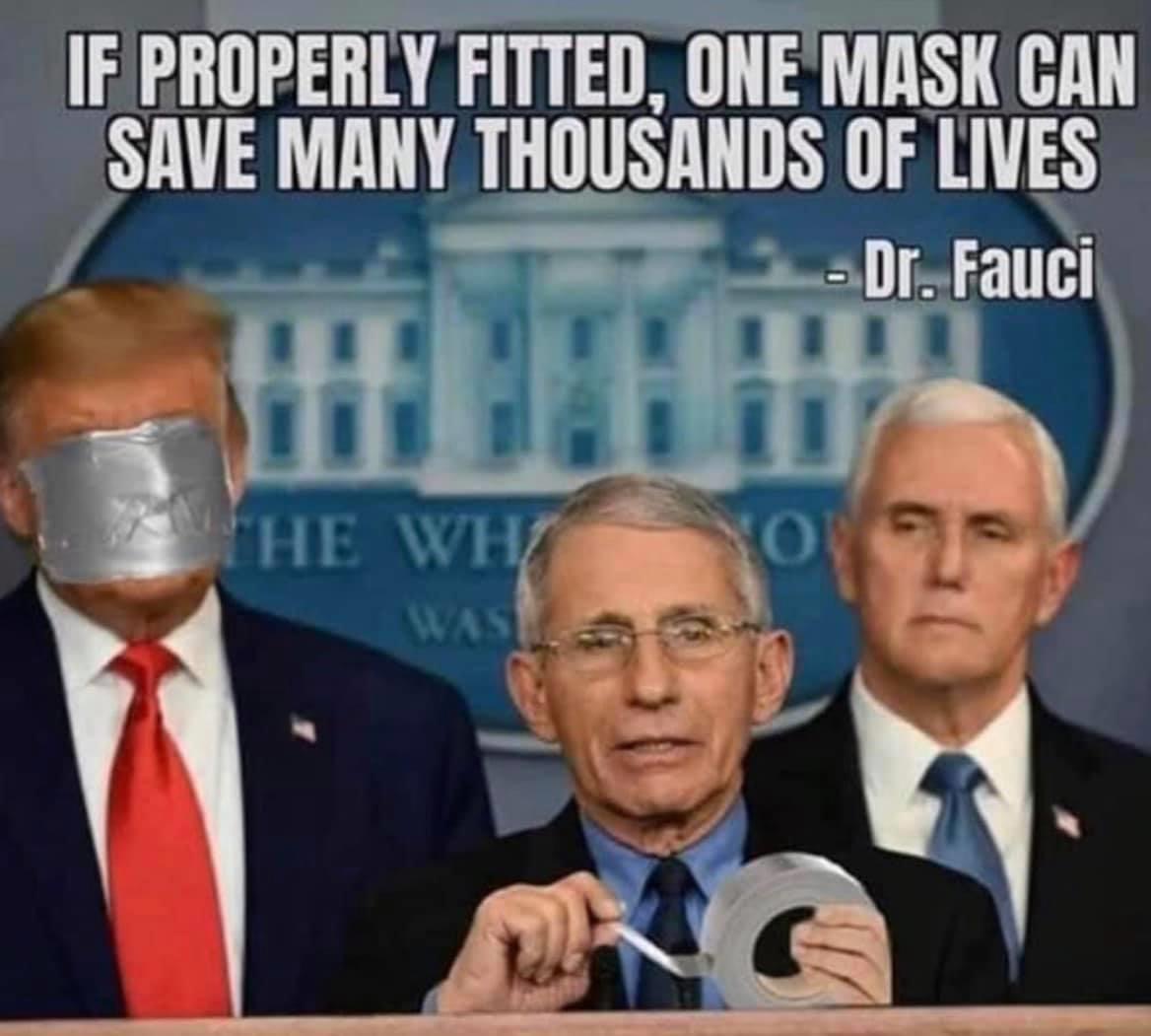

City officials also strongly advocated for face coverings, which were at first optional and soon required by a mayoral order — the country's first at the time, Navarro said.

"They were the one city that put a lot of stock in masks," he said.

With the pandemic still raging across the globe during World War I, the mask also became a symbol of "wartime patriotism."

"The man or woman or child who will not wear a mask now is a dangerous slacker," a public service announcement from the American Red Cross said at the time, according to Navarro's research.

That, however, did not stop people from defying the order — 110 people were arrested and given a $5 fine in one day in October shortly after the measure went into place, improperly wearing a mask or not wearing one entirely, according to the center's research. Over time, the jails were overcrowded with people failing to adhere to the rules. However, most cases were later dismissed.

By the end of October, there were 20,000 cases and more than 1,000 deaths. However, as the days went on, the city saw a dip in newly reported cases, which prompted officials to begin to reopen the city and rescind the mask order. By the end of November, officials believed the city had stabilized.

ey were flattening that curve'

But three weeks after that celebration of removing their masks, the city saw a dramatic resurgence. Officials at first rejected the idea of reopening the city and suggested residents could voluntarily wear face coverings.

But shortly after the New Year in 1919, the city was hit with 600 new cases in one day, prompting the Board of Supervisors to re-enact the mandatory mask ordinance. Protests against the mandate eventually led to the formation of the Anti-Mask League. The detractors eventually got their way when the order was lifted in February.

San Francisco's ambivalence to quarantine measures ran counter to other U.S. cities, though. Navarro said Los Angeles, for instance, implemented strict social distancing and face coverings about a week before San Francisco did and its measures stayed in place for weeks longer.

Navarro said that many cities often became complacent once they saw a dip in cases, and when a resurgence happens residents often question the public health guidance.

"They were flattening that curve; they just weren't realizing it," Navarro said. "A lot of people thought, 'Well, what did we go through that for? It did have an impact, they just didn't know it."

As Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation's top infectious disease expert, put it in March, "If it looks like you're overreacting, you're probably doing the right thing."

Back during the Spanish flu, San Fransisco's failure to take swift action and the decision to ease restrictions after only a few weeks had huge ramifications. With 45,000 cases and more than 3,000 deaths, the city was reported to have been one of, if not, the hardest-hit big city.

Roughly a century later, the San Francisco Bay Area imposed the nation's first stay-at-home order and other restrictions when coronavirus cases were rapidly growing, placing a spotlight on its pandemic response again. Those aggressive actions are credited with saving lives, avoiding the scale of the tragedy found in New York City.

Mayor London Breed said she took heed of history and implemented an order last week requiring anyone setting foot on the streets of San Francisco, outside their homes, to wear a face covering.

Breed told MSNBC's Chris Hayes in an appearance in mid-April that she has considered the city's history with past pandemics, such as the HIV/AIDS crisis and the Spanish flu when deciding to ease restrictions.

"Just because San Francisco is being praised for flattening the curve, we're not there yet," she said. "And so we cannot let up just because for some reason we believe that we're in a better place."

[Source]

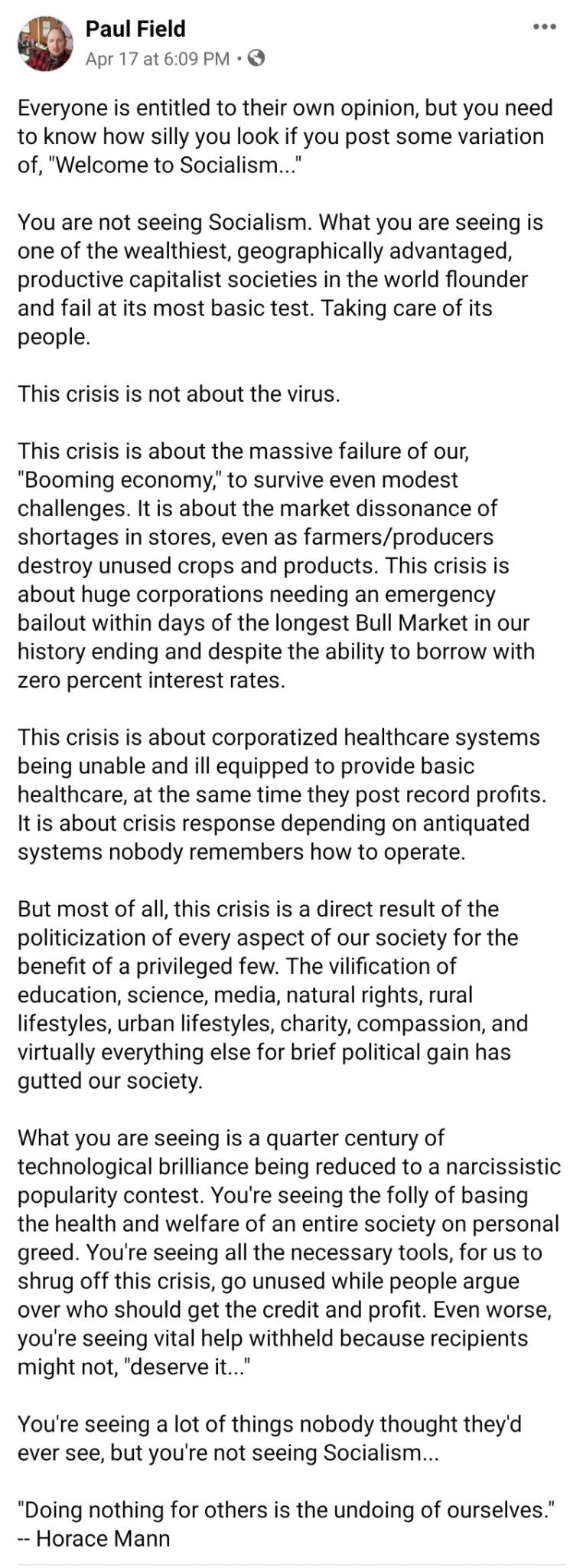

Ezra Klein, writing at Vox, on Marc Andreeson's "It's Time to Build" call to arms:

Which goes to a problem that afflicts governance at all levels of America: If you live in a vetocracy and one of your two political parties actively wants the government to work poorly, the government will work poorly. And so it does.

I don't think that'll be enough. So let me end with my answer to Andreessen's question: What should we build? We should build institutions biased toward action and ambition, rather than inaction and incrementalism. […] At the federal level, I'd get rid of the filibuster, simplify the committee system, democratize elections, and make sure majorities could implement their agendas once elected. As I've argued for years, we should prefer the problems of a system where elected majorities can fulfill the promises that got them elected to one where elected majorities cannot deliver on the promises that the American people voted for. The latter system, which is the one Americans live in now, drives frustration and dysfunction.

Full-throttled endorsement for this basic notion from me—knowing full well that political tides ebb and flow. Let the party in power try new things. If they turn out to be unpopular, the tide will change and so too will the laws and policies. Conduct politics more like we do science: try new ideas and see what happens.

I mean really?

Fuckwits with firearms

Fuckwits with flags

Fuckwits in pickups with Confederate flags

Gov. Whitmer's order for Michigan citizens to stay home, they said, was tyranny (SPOILER: if you can gather in public and accuse the government of tyranny without fear of arrest, it's not tyranny).

They repeated Ben Franklin's claim that 'security without liberty is called prison' (SPOILER: if you can drive your pickup to Lansing, Michigan, you're not in prison and you have liberty).

They chanted "Lock her up!" and "Keep America Great!" (SPOILER: if your nation was warned a pandemic was coming and didn't bother to prepare for it, your country isn't all that great, and a populace that wants to lock up a governor for trying to mitigate that pandemic isn't particularly great either).

They also gathered to block traffic in front of a hospital. Seriously, during a goddamn pandemic, these fuckwits thought it was cute to block the emergency entrance to a hospital.

Jesus suffering fuck. —gregfallis.com

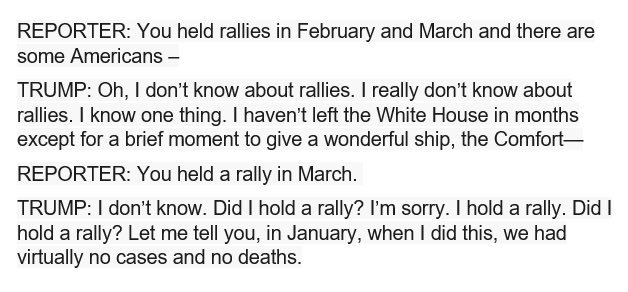

A recent profile in the New Yorker of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell quoted a staffer as claiming that behind closed doors McConnell has described Trump as "nuts." Democrats should demand to know if the Republican Senate mastermind truly believes that the president is impaired, and force McConnell to choose between yet more lies and the future of his country.

Democrats should also get over their concerns about angering Trump supporters. Anyone who continues to applaud Trump's weird and reckless disregard for humanity at this point is beyond the limit of rational persuasion. Trump supporters live in a hallucinatory dreamscape under the authority of a maniac. Let them have their anti-social distancing rallies, and allow them to believe that Barack Obama invented COVID-19 shortly after he was born in Kenya.

Rational Americans need to stop enabling this abusive and deranged presidency. Declare Donald Trump insane and, at long last, bring an end to our era of malignant normality.

Trump's lies are so brazen that it is now common for politicians and the media to talk about him lying, a word that would not have been used in days gone by but replaced by euphemisms. Is it only a matter of time before they start openly questioning his sanity instead of just whispering it behind closed doors? – Mano Singham/Freethought Blogs

Not surprising, considering these folks always were a few screws short of a hardware store.

When a society laments the loss of an economy more than it laments the loss of human life, it doesn't need a virus. It is already sick."

When a society laments the loss of an economy more than it laments the loss of human life, it doesn't need a virus. It is already sick."

"So, You Never Really Were 'Pro-Life," Were You?" from John Pavlovitz:

…and is, unfortunately, happening again.

From I Should Be Laughing:

We've been here before, you know, and clearly, we have learned nothing.

Picture it. America, 1918. The first World War was winding down and officials across the country were under enormous pressure to sell war bonds. But how do you attract attention to your bonds? Hold a parade in major cities to rally the public behind the war bond effort.

Trouble is, or was, America was in the throes of a pandemic—the Spanish Flu—and people were dying all over the place; when it was all said and done 675,000 Americans died of the Spanish Flu—50 million people globally—compared to 116,708 Americans killed in World War I.

Doctors were at a loss as to what to recommend to their patients; many urged people to avoid crowded places or simply other people, and also told people to keep their mouths and noses covered in public.

Sounds vaguely familiar, no? That September 1918, in Philadelphia, 600 sailors and 47 civilians had been diagnosed with the flu, and some had already perished. But, hey, there were bonds to sell the fund the war, and on September 28, 1918, Philadelphia held a parade to sell war bonds.

On the 28th, a line of Boy Scouts, marching bands, women's auxiliary groups, and troops 2 miles long wound its way up Broad Street in front of a crowd of over 200,000 people. Within three days, every bed in Philadelphia's 31 hospitals was occupied. Within a week, 45,000 citizens were infected, and the entire city had shut down. By the second week in November, 12,000 Philadelphians were dead, and the phrase "bodies stacked like cordwood" had become commonplace among the survivors. Within six months, 16,000 were dead, and 500,000 Philadelphians had fallen ill with the flu.

Now, I don't wanna bash Philadelphia, because that wasn't the only city to hold a parade or to urge citizens to come out in droves and mingle with one another, but …

Take Milwaukee, for example; they had the lowest death rate of any large city in America during the pandemic, because the city's health commissioner, Dr. George Ruhland, had ordered schools closed, saloons and public spaces shut down, and told people to stay home.

And yet here we are again, in the midst of a pandemic where we are told that social distancing, self-isolating, will stop the spread of COVID-19 and we have not learned one goddamned thing.

I swear Twitter just needs to just shut down Orange Caligula's account for violating any number of their Terms of Service. But if the Russian Wig Stand's call for armed insurrection against the governors of certain states won't trigger it, nothing will. #complicit